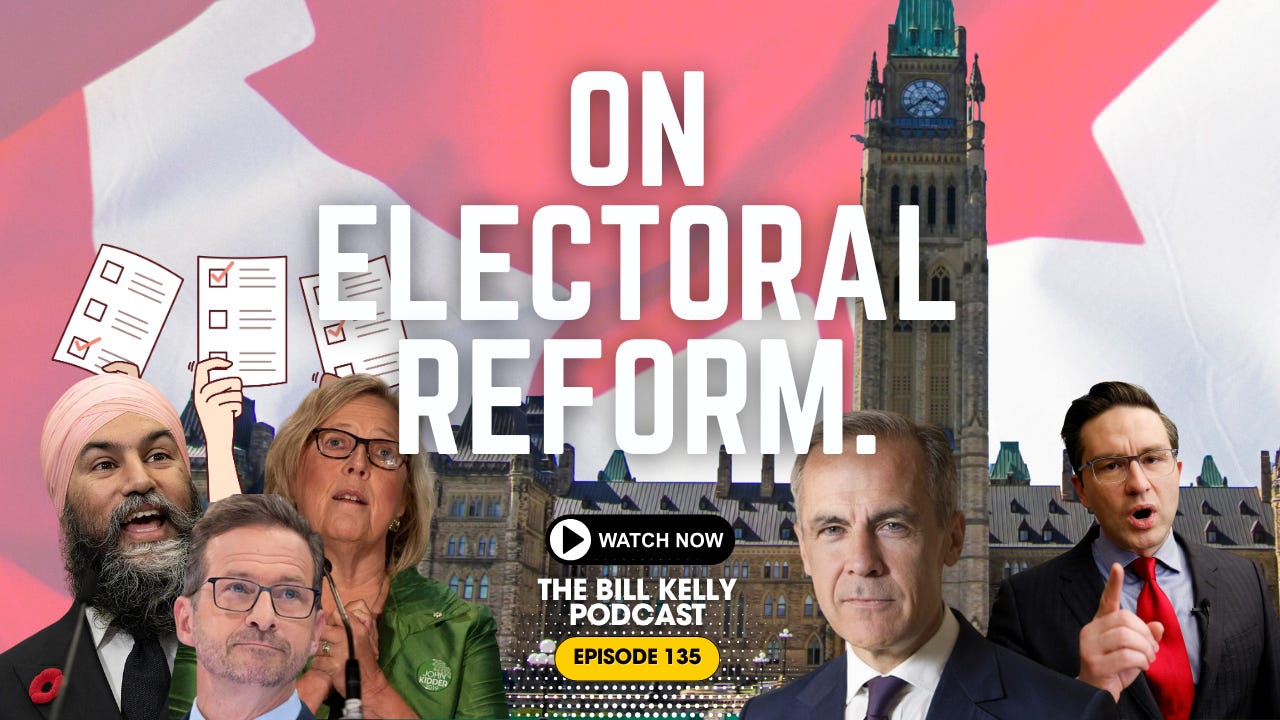

The Problem With Democracy (A Brief History): On Electoral Reform in Canada

Read Episode 135 of The Bill Kelly Podcast

We’ve just come through another Canadian federal election, and once again the conversation has turned—predictably—to electoral reform. It’s the same post-election ritual: questions about fairness, representation, and whether our system actually delivers the democracy we believe in.

So… is there a better way to do this?

It’s a question I’ve asked countless times—back in my radio days, on this podcast, and in conversations with people across the political spectrum. It’s not a simple one. But to even start finding an answer, we need to understand the system we’re working with—and how we got here.

This isn't just idle speculation. The question of how we choose our leaders has roots that go back centuries — to rebellious English commoners, frustrated Founding Fathers, and all the way to our modern House of Commons (yes, it’s called that for a reason). So let’s dig in — not just into our current system, but into some of the alternatives, and the bigger picture of what it means to elect people in a democracy.

A Quick History Lesson (You’ll Want to Stick Around for This)

Canada’s political DNA comes directly from the British parliamentary system — a structure that emerged from centuries of power struggles between monarchs and the people they governed. After enough kings made enough bad decisions (King John, anyone?), a deal was struck: let the commoners have their say, or risk losing the whole system.

Thus was born the idea of representative government. The "House of Commons" in the UK (and later in Canada) quite literally referred to a chamber for the common people. But don’t kid yourself — the elite still kept one hand on the wheel. The House of Lords in Britain, and the Canadian Senate here at home, were created to “balance” the will of the people with the oversight of the so-called educated class.

You might think things have evolved since then — and they have, in some ways. But the underlying tension remains: how much power should the public have? How do we ensure fair representation? And how do we adapt a centuries-old system to a modern world that’s more diverse, more informed, and frankly, more complicated?

What Kind of Democracy Are We Actually Running?

Here in Canada, we use what’s called a First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system. You’ve heard the term. It’s simple enough: whoever gets the most votes in a riding wins the seat. It doesn’t matter if they get 30%, 40%, or 51% — if it’s more than the other candidates, that’s good enough.

In a two-party system, FPTP isn’t too bad. But as anyone paying attention knows, we don’t live in a two-party world anymore. With the Liberals, Conservatives, NDP, Greens, Bloc Québécois, People’s Party, and a host of independents and fringe parties, the vote often gets sliced and diced in ways that leave a lot of people feeling unrepresented. A candidate can win with less than a third of the vote — and yet still hold full power in their riding.

That brings us to the crux of the debate: Should we be doing this differently? A lot of folks think so. Electoral reform has come up repeatedly, federally and provincially. Remember 2015? Justin Trudeau promised it would be the last election run under FPTP. That didn’t pan out. A committee was formed, consultations were held… and then? Crickets. Why? Because reform is hard. People are wary of change, and politicians who benefit from the current system have little incentive to overhaul it.

Still, it’s worth knowing the alternatives. Let’s walk through them.

1. First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) – What We Use Now

How it works: The candidate with the most votes in a riding wins — simple as that. You don’t need a majority, just more than anyone else.

Pros:

Easy to understand and execute.

Clear winners in each district.

Tends to produce majority governments (which means more stable governance).

Cons:

Voters can feel their vote was “wasted” if their candidate didn’t win.

Encourages strategic voting ("I’ll vote for Candidate B, even though I prefer C, just to stop A").

Can produce “false majorities” — where a party gets 100% of the power with only 30–40% of the vote.

2. Ranked Ballot (aka Instant Runoff Voting) – Voters Rank Their Preferences

How it works: Voters rank the candidates in order of preference — first choice, second, third, etc. If no one gets over 50% of the vote initially, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed according to second choices. This continues until someone breaks 50%.

Pros:

Helps elect candidates with broad appeal.

Reduces vote-splitting (no more punishing parties with similar platforms).

Still maintains local representation — each riding picks one MP.

Cons:

Slightly more complicated to administer.

Some voters may not understand or trust the process.

Results take longer to count.

Fun fact: Every major political party in Canada already uses this system to elect their leaders. But apparently, it’s too radical for the rest of us?

3. Proportional Representation (PR) – Parliament Mirrors the Popular Vote

How it works: Parties receive seats in proportion to the percentage of the vote they receive nationally or regionally. So if Party X gets 30% of the vote, they get 30% of the seats in Parliament.

Variants include:

Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP): A hybrid where you vote for a local MP and for a party. Some seats are filled by direct election, others are filled based on party vote share.

List PR: You vote for a party, and parties fill seats from a pre-ranked list of candidates.

Pros:

More accurate reflection of voters’ wishes.

Encourages collaboration between parties (coalition governments).

Smaller parties gain a fairer chance at representation.

Cons:

Weakens the link between voters and local MPs.

Often leads to minority governments and fragile coalitions.

Can empower fringe parties if thresholds are low.

Biggest concern: Rural areas worry they’ll lose influence. Urban centers, with their larger populations, could dominate the national conversation.

So… Is Change Coming?

That’s the million-dollar question. Every few years, we get a surge of interest in electoral reform — often driven by frustration with election outcomes. But meaningful change? That’s a tougher sell.

In Ontario, for example, the McGuinty government held a referendum in 2007 on adopting MMP. It failed. British Columbia has tried similar efforts — also failed. Why? Because we’re creatures of habit. We might grumble about our system, but when push comes to shove, we tend to stick with the devil we know.

There’s also political inertia at play. If you just got elected under the current system, why would you change the rules and possibly lose your job next time? Electoral reform usually dies on the desk of the very people who benefit from the status quo.

The Real Challenge: Political Incentive

Let’s be honest—politicians who win under the current system rarely want to change it. Why would they? If First Past the Post got you elected, why risk your seat by introducing a system that might not work in your favour next time?

But there’s also another side to the story: under PR, fringe or micro-parties that never win a riding could suddenly gain seats in Parliament. For better or worse, that’s part of the deal. Some say it would give a voice to the voiceless. Others say it would create chaos.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

With each election, the debate flares up again. And then… fizzles. Most of us shrug and say, “Yeah, it’s not perfect—but it’s what we’ve got.” There’s a certain comfort in the familiar—even if the familiar isn’t fair. The truth is, no system is flawless. As Winston Churchill famously said, “Democracy is the worst form of government—except for all the others that have been tried.”

“Democracy is the worst form of government—except for all the others that have been tried.”

- Winston Churchill

There are lessons to learn from other countries—France, for instance, uses runoff voting. Germany employs a mixed proportional system. Reform can work, but it requires political will and public trust.

Until then? We’re left with the system we’ve got. Warts and all.

So the onus falls on us—the voters. We have to do our homework. We have to show up. We have to choose wisely.

Because if we get it wrong—and sometimes we do—we’re the ones who have to live with the consequences.

What do you think? Should Canada overhaul its voting system—or stick with the devil we know? Drop a comment below. I want to hear your take.

Until next time—stay in touch, and stay informed.

— Bill Kelly

FURTHER READING

Record-tying number of candidates running in Ottawa riding of Carleton

Administration as lord protector of Oliver Cromwell

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell/Administration-as-lord-protector

Behind the Ballot Box: Citizen’s Guide to Voting Systems

I think we need to change no matter what the cost. I believe it was Winston Churchill who said "Peope who cannot change, change nothing." Nothing gets changed with out change. Nothing goes forward without change. Pedaling a bicycle is change compared to sitting on your bicycle and doing nothing. Putting one foot in front of the other is change compared to standing in one spot and going nowhere. Let's change now and go somewhere. Let's do it now.

This does not sound like Bill. Can l ask who this is?